Listen up, friends!

As much as I enjoyed writing this piece (I really did), it includes some intense info.

A content warning marks the brief section. You are invited to skip to the next heading—I think the piece is cohesive without it.

Light Hive offers essays on mindfulness for complex times. Subscribe for applied takes on Buddhist thought, through the lens of a recovering academic and queer, transracial adoptee.

She loved Jim Morrison, John Lennon and, for a reason I could not fathom, me.

She would not graduate from the all-girls Catholic college preparatory we both attended. Saying “fuck you very much” to the Old Testament/New Testament teacher as she opted for Starbucks over class was, in the end, not cool for school.

She was the first person to talk to me about Buddhism. I remember her telling me one night about what it meant to look at the moon, not the finger.

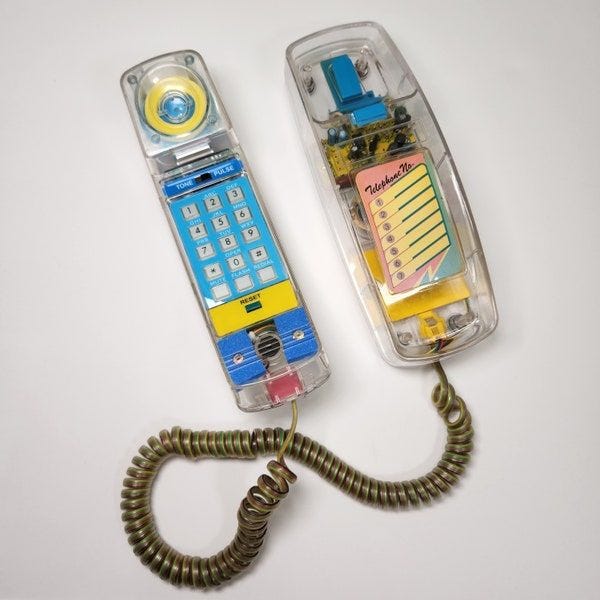

I had absolutely no idea what she was talking about. No bother. I was so enamored, so grateful to have a see-through phone that brought her voice, her world, into my ear.

I could hear the most incidental sounds of her materiality. I could hear her shuffling around. I could hear her lips release a joint after a long drag. Sometimes she’d put the phone down to get something from the kitchen. Even her receding footsteps felt like proximity, because it meant she would return and again choose to bring me close enough to hear her breathe.

When people lip-sync, it’s almost like a possession. One voice takes over another’s body. Our calls were something more agential: an ongoing permission to harmonize.

Deeply listening to someone else can be a political act that reclaims our bodies and our relationships. It is difficult to listen these days; our urgency leaves little bandwidth for others. And of course, the quality of our listening changes based on the constraints we face.

But the practice remains: listening restores embodied presence that makes collective action possible.

“Children, behave”

Noise distracts and fragments our attention.

Consider: you’re one-quarter-listening to a rando provide an opinion at a party. Music is playing and you want to be, like, social or whatever, so you’re nodding at intervals you hope make sense. Your mind, meanwhile, is thinking gosh it’s been so long since I’ve heard this song. The 80’s version was fine but the world needs more cricket music and, suddenly, someone says your name.

We are trained to respond to cues. In this sense, listening has always been about survival. But that’s not the kind of listening I’m referencing.

I’m pointing at a flexible, responsive mind state focused on the deliberate cultivation of concentration. This is akin to the Buddhist idea of samadhi, a kind of “mental unity.”

As ever, it’s impossible to pay attention to everything. But cultivating an ability to listen to someone or a situation, rather than for a specific data point or threat, invites an intentional reclamation of our attention.

It’s hard, I know, that’s why I’m writing about it.

It doesn’t help digital technologies work via overwhelm. When our day-to-day feels like a flood of notifications that scatter consciousness, silence can be incredibly uncomfortable. We want to fill it. Avoid it. Scroll through it. Our minds wander and wonder what could possibly be wrong with us as individuals.

It makes more sense to self-pathologize than critique external patterns and systems. One feels vague and amorphous. “Capitalism.” The other…well, there’s medication for that.

And I take medication, so I’m not judging. But the general trend remains. Most look outward to the experts, the professionals, the scientists, because looking inward might mean realizing our interdependence means we are “society.”

Unlike the scattered attention that digital overwhelm creates, a samadhi practice cultivates focus. It's the difference between listening while mentally composing your response (I do this all the time) and listening to understand what the moment needs. Maybe nothing needs to be said.

The fragmentation of awareness isn't just personal—it's political. If we can't listen to ourselves, it’s difficult to soothe ourselves. If constantly dysregulated, it’s hard to build the relationships that sustain movements for broader change.

This is why fully inhabiting one’s own body and offering presence to another is a political reclamation. Listening isn't passive; it's active resistance to a political economy built on fear, competition, and scattered consciousness. Individual practice becomes relational practice becomes collective, embodied, presence. We become harder to fragment, harder to control.

Queers have always needed to be vigilant, paying attention to each other’s movements, voice, speech. We also needed to be wary of threats.

Viral justice is an invitation to listen anew to the white noise that is killing us softly, so that we can then make something soulful together, so that we can then compose harmonies that give us life. — Ruha Benjamin

“And Watch How You Play”

We wanted to find each other so much, we stopped to look and listen.

Queer folks have often needed codes to find each other. Listening for the message and reading between the lines was about surviving threats and negotiating desire within constraint.

Some might have heard of the “Red Scare.” In 1952, the House Un-American Activities Commission was also investigating and interrogating gay men in what would be called the “Lavender Scare.”

Women too, but hardly anyone took female sexuality seriously. This meant book depictions of “close female friendships” could feature emotional resonance and physical touching, especially if the overall narrative concluded with them separated for reasons like death or compulsory heterosexuality.

Writers like Vin Packer took advantage of this friendship loophole. After her release of Spring Fire in 1952, the publisher Gold Medal Books was overwhelmed by mail. Housewives who previously thought themselves ill, inadequate, or perverse, now realized they were parched.

One of those letters was from a young Ann Bannon. Like an absolute stud, Packer invited Bannon to visit Greenwich Village. There, they hung out at lesbian bars: dark, dingy places that were password-protected to guard against police raids.

Bannon would later recall her sense of surveillance and fear.

I would sit there in the evenings thinking, ‘What if [a raid] happens tonight and I get hauled off to the slam with all these other women?' I thought, 'Well, that would do it. I'd have to go jump off the Brooklyn Bridge.' As easy as it might be if you were a young woman in today's generation to think that was exaggerating, it wasn't. It was terrifying.

These experiences would fuel Bannon’s career, with novels that included racialized and butch lesbians as well as Beebo Brinker (a proto-Shane McCutcheon), the eventual namesake of her series.

All this time, Bannon told her husband the stories she wrote were about girls. This ensured he would never read anything she wrote.

While the technologies of surveillance have evolved between Bannon's era and our current moment, the dynamic remains: power resides in the watching, just as power resides in the codes.

*** content below includes family violence. It’s ok to skip to the next section ***

I haven’t experienced the raids Bannon described, but I empathize with the terror. As a teenager, I understood codes, coercion, obfuscation, and power.

Once I began menstruating at 11, my mother was determined to acquire mixed-race grandchildren. The easiest route would be to inseminate me, her adopted “geisha.” I wanted out but was unsure how, so my goal became to attend college out of state. I needed to keep my head down, grades up, feel nothing, and get through graduation.

And so my high school crush, brimming with agency, did the Time Warp into my life at a critical juncture. When we went out (or my older brother was home), men would make comments about how much she looked like Angelina Jolie. And then she’d cuss at them, sometimes running at them waving her arms and making animal noises, and return to grab my hand. It was fun to see the cat-callers scurry. It was life-saving to be held.

My junior and senior years, I’d do homework until the house was quiet. When there didn’t seem to be any one around, I’d use our second landline and my hidden, see-through phone to call her.

Back in the olden days of when I was in high school, some homes had multiple landlines. Fancy (often office) phones could switch lines with button. In my case, I was plugging an actual phone into a second phone jack in the wall. Anyone in the house could connect any phone to the second line and listen.

My mom had done it before. I usually heard the muffled double click, and could redirect or reframe conversations on the spot.

Usually.

The last thing my first girlfriend said the night my mother eavesdropped was “Do with that what you will.” At that, my mom burst into my bedroom (I was too disrespectful to ever have a lock) demanding a translation, as if the ambiguity itself wasn’t clarity enough. My mom repeated the line as she beat me with the phone until the transparent casing cracked. Then she trashed it.

So I got a new phone.

Later, when some girls at my school were getting cars or plastic surgery for graduation, my girlfriend got me the morning after pill. She had gone into Planned Parenthood and told my story as her own.

This was not possession. She heard me. Of course she had permission to speak as my body.

Holding on to One Another’s Hand

Listening for what is needed and what is noise in times of crisis.

“Hey there, my name is Logan and I see you are losing a massive amount of blood. Lucky for you, I learned how to make a tourniquet with this ballpoint pen and random stuff from my bag about seven minutes ago. May I touch you?”

The instructor interjected. “You’re not going to have time to say all that.”

My Community Emergency Response Team (CERT) Training has been stellar. I absolutely recommend it to anyone interested in feeling a bit more prepared in crisis situations. Each free CERT training program is focused on the most likely disasters in your area. As one might imagine, the person who thinks games are social laboratories also finds hands-on tutorials and scenario drills very helpful.

With added gravity: “Hi, I’m Logan and I’m here to help. May I touch you?”

“She’s going to bleed out. Other people need you.”

In an emergency, I’d likely defer to his urgency. His goal is utilitarian: greatest good for the greatest number. He’s been doing this for decades and is training me in skills I might use in the future. He isn’t wrong.

And I’ve been training to, as much as possible, see what’s arising separate from the urgency. That moment was bloodless.

To “triage,” we learned in a previous class, means to prioritize based on need. I made eye contact with the person who hadn’t yet been heard and pared down to the most necessary.

“May I touch you?”

“Yes.”

Readiness to respond requires a kind of listening that so many forces seek to fragment. The technologies that connect us can also keep us comparing, consuming, afraid, and isolated. This gray zone is why it benefits us to discern necessity and noise.

I started this essay Thursday, finished a draft Friday, and edited Saturday, June 7th, the day the National Guard was called into Los Angeles to quell what the White House is calling an “insurrection.”

I think a lot of us think we’re alone now. Who is left to protect us?

Based on my experience, it’s us. We are the safety we create. The more listening we can do, the better we can identify allies, show up for each other, and savor the things worth fighting for.

So I’m not going to tell you what I think about the moon and finger thing. Instead, I’ll say: keep your eyes, ears, and beating hearts open.

Takeaway Practice

A listening practice.

I have often advocated for meta-communication: discussions on language, meaning, oriented toward restoration and repair. I like scheduling these, but meta-communication can happen organically within a conversation.

The goal isn’t to interrogate someone, because maybe they don’t know what they mean. Sometimes people just need to process out loud—a kind of verbal ventilation—and that's okay, especially when you as listener understand what’s happening.

The goal is to listen for the intended present meaning. What does [a word, a phrase, a reaction] mean for them?

If you liked this, consider checking out:

Bio

Logan Juliano (they/them) holds a PhD in Performance Studies. Through Light Hive and as co-editor of Notes from the Inflection Point, they write to share reflections and practices amid ecological and sociopolitical uncertainty. They are aware it is summer.

What a deft piece of writing, Logan. I love the weaving together of your own story, the queer herstory transmission, and the political framing of deep listening (which I'd never thought of before but now it makes so much sense I can't believe I missed it!). And chef's kiss, Tommy James and the Shondells!

This is such a powerful read; thank you for writing & sharing it.