Stop burning out for a revolution that needs you

“All our everyday efforts have one objective: happiness.”

Activists are keeping neighborhood watch, making monarch butterflies and resource databases and vats of wheatpaste, drafting talking points for city council members, 3D printing whistles…and burning the fuck out.

Is your exhaustion what justice feels like?

When Audre Lorde said self-care is a political act, she didn’t have bath bombs and Esalen retreats in mind. She was talking to people at the intersections: women of color going to work amid structural violence, organizing their lives and those of their children or spouses, and still fighting for a better world.

The people who know systemic exhaustion and still act are deeply needed. For that reason, this piece advocates for a personal and collective kind of care.

Stress and suffering

In all hands on deck moments, we must remember many hands make light work.

Why do we work ourselves into the ground? Fear of not doing enough. Grief we don’t have time to process. Rage that feels like the only appropriate response.

Social justice and human rights (SJHR) activists are not immune from burnout, no matter how anti-capitalist they are. Martyrdom is a symptom of trickle-down terrorism: fear as a self-governing tool, depletion as personalized healthcare policy.

Cher Weixia Chen and Paul C. Gorski found two primary reasons for burnout among 22 SJHR activists in paid roles within funded organizations: underappreciation (crap roles, low pay, little social regard) and a “culture of martyrdom” that makes self- and organizational-care a betrayal.

And so when the people paid (however poorly) and trained to do this feel “frayed all over,” the result is natural. People on the sidelines look at on-the-ground activist-organizers and shake their heads. “I could never do that much.” So they don’t.

Some think, “I’d like to help, but I don’t know how to start,” presuming a higher bar than just starting where they are with what they had. So they won’t.

Or: “You must be delusional for thinking you can change things,” as if rapid responders weren’t simply triaging a broken social contract.

I encourage folks on the ground: give yourself the oxygen mask of grace. Then help others put theirs on.

We are finite and everything is impermanent. In The Way of Tenderness, Zenju Earthlyn Manuel writes we must “carve a path through the flames of our human condition. We must see it for what it is, and bow to it—not a pitiful bow, but a bow of acknowledgment.”

Manuel: “we are not superheroes; we are human beings.”

Truth, justice, and the American way

An adopted immigrant made lack of rest the American way.

Superman’s creators were Jewish immigrants fleeing European persecution in the shadow of the Great Depression. They built a mythology where an alien could assimilate by never processing loss. Clark Kent would work, without sleep or rest, under the threat of having to face his own separation trauma. Any proximity to home or grief is his Kryptonite.

Grief and loss is characterologically embedded into “super” narratives, often as something to be held at a distance. Avengers: Endgame was a movie about heroes unable to bear the grief of losing half of all life, so they undid Thanos’ attempt to address the limits to growth and overpopulation.

As social totems, heroes—civic or super—represent the dream of the individual who can save others without slowing down. Few have time to sit with their own grief, their own planet, with careful attention. How many avoid rest because slowing down means recognizing the material conditions they would rather avoid?

A contrast in clear-seeing and making-do: Alabama, sometime before 1950.

One day, about 15 kids were playing outside Seneva’s modest home when a storm began. The storm was strong enough to terrify the kids and bring them indoors, fierce enough to begin lifting the house from its foundation.

One could have asked, “Why is this house so shitty? Why is the storm this intense? Who are all these damn kids and why are they here?”

Seneva had the children hold hands and move toward the parts of the house losing their connection to the ground. The weight of about 15 children and one woman, determined that if she left her home the home would come with her, held the house to the earth.

Standing her ground inspired one of the children, her nephew, later Congressman John Lewis, to remark:

That is America to me—not just the movement for civil rights but the endless struggle to respond with decency, dignity and a sense of [siblinghood] to all the challenges that face us as a nation, as a whole.

Seneva rallied 15 terrified children to keep a house grounded in a storm. The lesson is about the collective weight of a congregation, not an individual.

So bow to your finite humanity. You can only do so much. Figuratively speaking, give up the cape.

Or, maybe, put a real one on.

There are other ways than the American way

Movements that don’t practice collective imagination risk recreating the same oppressive structures with different names.

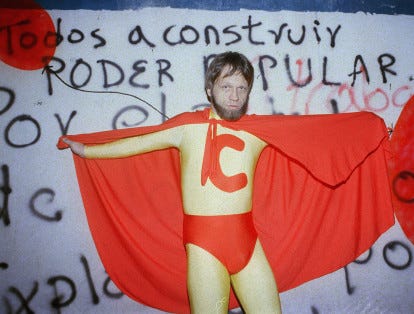

Travel with me through time and space to Bogotá, Colombia, in the early 1990s. This is a city of about 8 million people and staggering violence.

Some reports state that there were about 81 homicides per 100,000 residents in 1993, making it number one in global murder rates. This was in part due to localized crime networks, overseen by militias and cartels.

This was a capitol “hated by its inhabitants, who felt powerless and felt that in the future things would only get worse.”

Enter Antanas Mockus.

Mockus became mayor of Bogotá dressed as “Supercitizen”—but his actual governance was the opposite of superhero logic of catching bad guys or vengeance.

“All our everyday efforts have one objective: happiness.” He hired mime artists to regulate traffic instead of armed police. He asked people to voluntarily pay extra taxes, and 63,000 did. He held “A Night Without Men,” where women took over the city while men stayed home with family.

“People respond to humour and playfulness from politicians,” he wrote. “It’s the most powerful tool for change we have.”

Okay, but that was decades ago in a country that isn’t here, by someone with political clout. How could that possibly translate to now?

The stakes here, now, are why we must act from the fullest capacity of our collective potential. If clinging to individual heroism and predetermined certainties is a blocker, an antidote might provide:

a way for multiple people to engage,

uncertain outcomes,

practicing being with emergence without controlling it.

What does that look like?

Well, this frog, recently photographed in the Portland area, offers one visual.

I want to invite an even bigger hop, if you will, toward something less replicable and more emergent. Movements need people who know how to sit at tables together and imagine different futures—just as much as they need meme-able symbols like Superman and people in inflatable costumes.

Everything is situational, and this variability is exactly why I find tabletop games, live-action role-play, collaborative storytelling such rich territory.

Some organizers might see this a massive waste of time or one more thing to schedule. People are being kidnapped from their homes, homes are flooding, food assistance has been slashed, healthcare premiums are rising, rent bills and layoffs are rising. How dare I suggest play?

The play I reference isn’t escaping into a VR world. Staying material is the point: interacting with uncertainty, doubt, each other, to practice imagining futures beyond franchises and federal orders. To give each other grace and witness.

Some people need help starting action. Others need help slowing down. I offer, as I tend to do, play as the middle ground.

Play because you’re a human with agency, not a match struck and discarded.

A path of play

Your burnout won’t “earn” a revolution. Revolutions are won by communities that learned how to keep living together.

Play happens when failure, loss, grief, and love are equally acceptable possibilities. Here’s a simple offering:

Close your eyes.

Breathe.

Notice yourself inhabiting your time, your body. You aren’t “taking your time” (from whom?), you are experiencing it.

Eventually open your eyes.

This is a reclamation. Experiencing your life fully—all the messiness, disappointment, grief, and awe—is justice.

Still, games and geeky shit are my pet modalities.

So once you’re done, drop an invite to play something generative and easy to pick up into the group chat. Maybe Ben Robbins’ Follow, perhaps in conjunction with Jack Edward’s seasonally-appropriate quest Feast.

Play. Let it be, and may it be so.

The future will be built by those who remember how to stay human long enough to build it.

Thank you for reading. If this post resonated with you, please share it with others.

Light Hive explores embodied and engaged mindfulness in complex times. Subscribe for essays on personal practice, cultural analysis, and community care.

If you’re already subscribed, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. $8/month supports me and my writing.

If you liked this, consider checking out:

We struggle enough with coalition building. Burnout & irritability certainly doesn't make that job easier. Important reminder to breathe. Thank you.

Beautifully written, Logan